How did we source the material?

The first headache encountered by any project to digitise an historic newspaper is which edition do we use? To those unfamiliar with media history it may come as a surprise to learn that there is no single edition of a daily newspaper. Historically, most papers have published — and continue to publish — multiple editions in one day, including late editions, regional editions and weekly editions. While the content will be broadly the same between the editions, there will be some differences in the selection of news stories, advertising, and even seemingly trivial details such as the masthead. Which, then, is the ‘authoritative’ edition to use for digitization? Perhaps in an ideal world we would digitise all editions of the paper, so that researchers could see it in all its forms. Unsurprisingly, the costs of doing so make this a non–starter in most cases; digitizing just one edition of the paper is expensive enough. But there is also the experience of the end user to consider. Does someone searching a newspaper archive really want their results swollen by multiple editions? No doubt there are scholars who would derive benefit from this, but our experience shows that newspaper archives are used by a broad church of the research community, including family historians, science departments, and schools. Keeping the archive straightforward and non–confusing is vital.

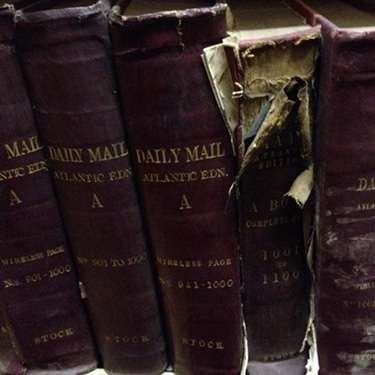

For content dating before the 1970s and the heyday of microfilming, most archives are digitised from the versions of the newspaper or periodical that were bound into annual or semi–annual volumes. These ‘library editions’ were produced by publishers precisely for preservation and collecting purposes. As Laurel Brake points out, these editions normally exclude ‘ephemeral, paratextual matter’ such as advertising wrappers, supplements, and in some cases even covers.2 library editions are, by necessity, the versions of newspapers most widely consulted in print, but it is important to note that they are no more definitive than other editions. From the 1970s onwards, most major UK newspapers instigated microfilming programmes to preserve their paper for archival purposes. Although many continued to publish bound library editions, microfilming represented a shift in the preservation process, with loose editions being filmed on a monthly basis. At the same time, most newspapers microfilmed their back issues of the bound library editions, so that they had a complete corpus of the newspaper on microfilm.

In the case of the Daily Mail Historical Archive, it is this in–house microfilm, owned by Associated Newspapers, which we have used as the basis for digitization. On the microfilm, the final London edition of the newspaper is the edition that has been used for filming, so in the majority of cases this is what the user will be viewing. Occasionally, where the final edition of the day was not available, we have used earlier editions.

Using the microfilm led to some problems caused by the medium. There were a number of issues, particularly in the early years of the paper, where the team determined that the filmed images were unfit for purpose; the original source was torn or damaged and should never have been used for filming; or the issues had been filmed from tightly bound volumes, causing excessive curvature and obscured text. In most such cases, we replaced the images using reels from an alternative microfilm edition created separately by the British Library. It is worth stressing that microfilm is not innately an inferior medium for digitization. If the original filming was done well and from well–preserved original copies, even decades–old microfilm can produce surprisingly good digital images.

Working our way through the microfilm threw up some surprising anomalies too, evidence of selection decisions made by earlier editors. During the General Strike of 1926, Fleet Street did not put out any newspapers. On the microfilm, the Daily Mail Continental Edition, published in Paris, plugs the gap. We elected to keep this in the digital archive, rather than have no edition available for the period of the strike.

Where available, supplements have been included. Supplements are defined here as components of the paper that have separate pagination from the main part of the newspaper. In print, these sometimes appear in the middle of the paper. This makes sense in terms of packaging the newspaper up as a physical object, to make it compact and easily foldable. In the digital edition it does not make sense to replicate the exact place in which these supplementary materials appeared, as it renders the page sequences extremely confusing, and sometimes splits articles in two. Users cannot pull out the magazine and other supplements to read the main paper uninterrupted, as they would in the material world. We have therefore placed supplements after the paper.

The Weekend magazine, included as a Saturday supplement from 1992, has been filmed inconsistently, and as a result we do not have a complete run in the digital archive. For cost reasons, it has not been possible to fill the gaps by scanning the missing issues. With regret, the primary focus of this project is the main paper. There are other necessary omissions. There are Scottish and Irish editions of the paper, as well as the Continental Daily Mail and the short–lived weekly US edition published from 1944 to 1946. There was even a Braille edition. Ultimately it has not been feasible to include these. In a related vein, the weekly Mail on Sunday began publication in 1983. Although under the same ownership as its daily sister paper, the Mail on Sunday is a separate newspaper, with its own editorial and journalistic team. Given this, and that its historical legacy is not as long as the Daily Mail, we felt justified in de–scoping it from the project. If there is significant interest, the Mail on Sunday may be added to the archive as an upgrade in the future. Finally, Alfred Harmsworth created no less than 63 ‘dummy’ editions of the Daily Mail before its official launch on 4 May 1896, to test his ideas about layout, visual impact, and balance of content. Only some of these ‘dummy’ editions survive, and they were never released to the public, so they have not been included in what is intended to be an archive of the ‘official’ newspaper.