Essays

The below essays are provided to introduce users to the material available in this archive, and to explain its importance to the study of the history of Northern Ireland. Each essay contains links that take you straight to the document being referenced (provided your institution has access to this material).

Introduction PDF

Dr Grace McGrath, Education, Learning and Outreach Office, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland

Dr McGrath provides a historical overview of the Northern Irish government, highlighting the importance of the Cabinet Conclusion Files. These files, summarising the key points discussed and the decisions reached during Cabinet meetings, offer insight into the government and civil service activities. They represent a full record of every debate and transaction for the entire duration of the Stormont administration and provide a continuous record of how the government actually worked.

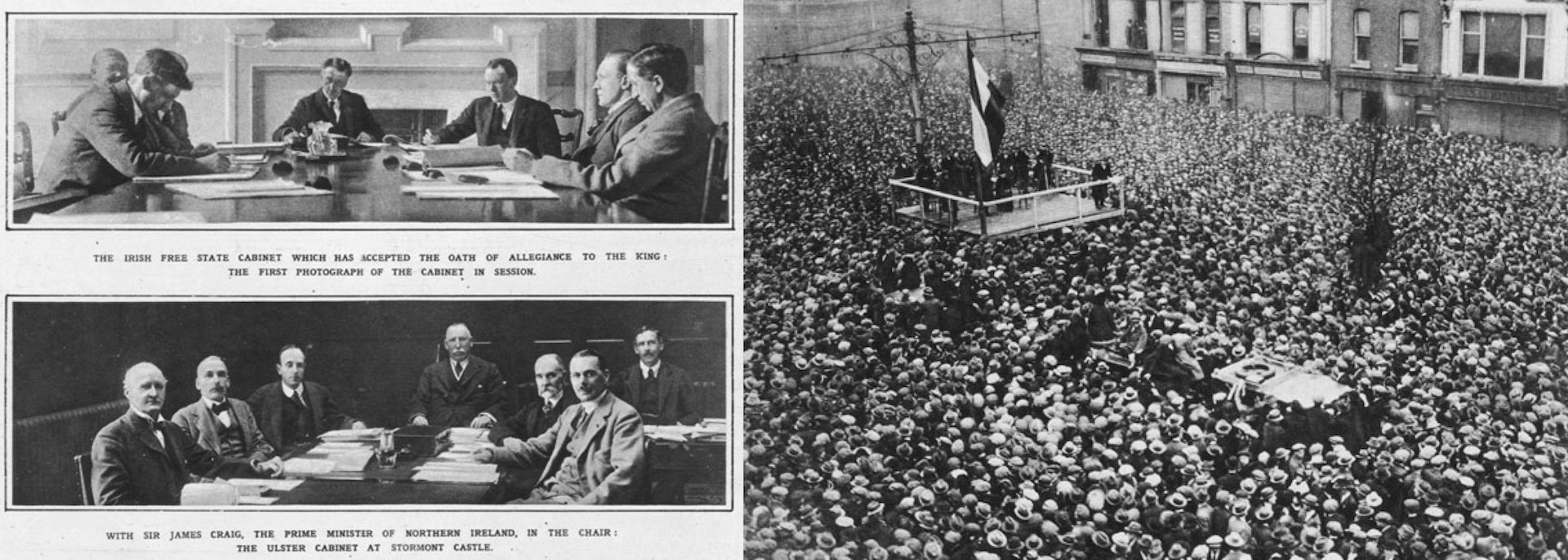

The Formation of the Northern Ireland State PDF

Dr Senia Paseta, St Hugh’s College, Oxford

The Government of Ireland Act of 1920 aimed to placate both nationalists and unionists temporarily, while introducing enough restrictions on both Irish parliaments to encourage eventual unity, and the attempts to create order and stability, which has begun prior to the act, reached new heights as sectarian tensions increased, with nearly 300 murders recorded in 1922.The Civil Authorities (Special Powers) Act of 1922, made permanent in 1933, included provisions for flogging, curfew, internment and was used almost exclusively against the Catholic minority. Economic distress, which had remained weak since the province’s inception, resultant in a consistently high unemployment rate, reaching 19% from 1923 to1930. This became a defining feature of Northern Ireland and contributed to the permanently strained and suspicious relationship between Protestants and Catholics.

Northern Ireland and the Second World War PDF

Dr Senia Paseta, St Hugh’s College, Oxford

Northern Ireland was slow to prepare for the war: no new factories were built and the munitions industry had the worst record for production in the UK during the early months of the war. Devastating German air raids demonstrated how underprepared the province was, the raid on Belfast of 15-16 April, 1940, resulted in the UK’s highest casualty rate in one night’s bombing. As the reality of war sank in the government began to respond to new demands and full employment was achieved in 1944. Despite the industrial development that aided the war effort (shipyards, aircraft factory, textile industry, etc), industrial unrest as greater in Northern Ireland than anywhere else in the UK and the conscription rate, which were not mandatory, remained low.

Sectarianism in Northern Ireland PDF

Dr Marc Mulholland, St Catherine’s College, Oxford

Nationalists were thought poorly of by Unionists and suffered discrimination as result. This sectarianism was described as: designed to preserve the power of the Unionists, defensive and particularly acute in those areas were Unionists were weakest, intended to preserve a perceived balance and precisely deployed at the local level. Northern Irish culture was deeply divided, where polarised political values and “gerrymandering”, the drawing of electoral boundaries to under-represent certain groups, was a reality. Although Northern Irish politics modernised, the divisions between Nationalists and Unionists only became clearer.

The IRA PDF

Dr Marc Mulholland, St Catherine’s College, Oxford

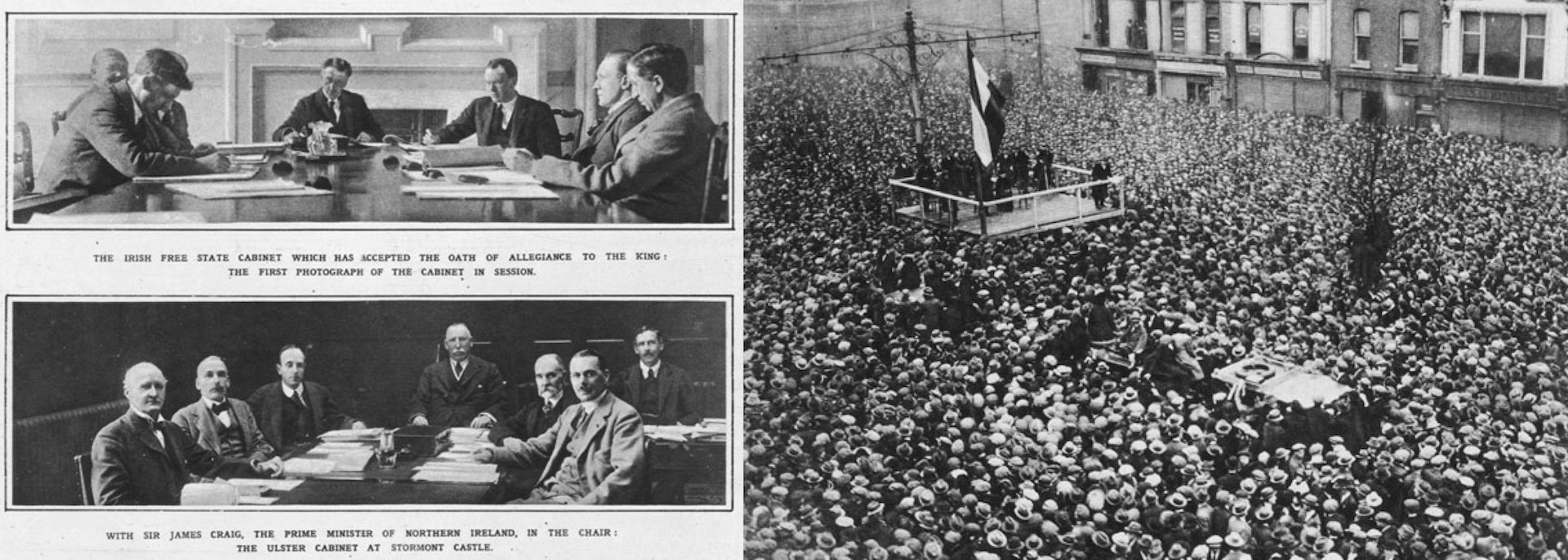

By 1920, a guerrilla war of independence was developing, with Baden Powell’s Boy Scout Movement on one end and the Irish Republican Army (IRA) on the other. The latter was not just a group of republican revolutionaries, but also champions of the Catholic nationalist minority, emerging as community defenders and provocateurs in the aftermath of three week riots following an Orange parade. The months following Bloody Sunday in 1972 saw the peak of the IRA campaign and the support it was able to generate and on May 29, 1973, the IRA ordered an immediate cessation of hostilities, a ceasefire which resulted in a quick reaction from the British government, who promptly released IRA internees. Talks held between the IRA and Whitelaw in July broke down within two days and hostilities resumed. Although the IRA played an important role in bringing down Stormont, it did not have the capacity to constructively influence and shape any alternative.

Civil Rights PDF

Dr Marc Mulholland, St Catherine’s College, Oxford

When Terence O’Neill became Prime Minister in 1963, 65% of Catholics felt that there had been a change for the better in community relations. O’Neill’s political vision was to re-configure politics and re-establish the Unionist Party altogether, loosening its relation to Protestantism. His hopes rested on the assumption that Catholics were gradually accepting the Northern Ireland state as legitimate; unfortunately it appeared to be more the case that Nationalists were demoralised, leading to the Civil Rights Movements. The most striking focus of Catholic civil rights discontent was Londonderry and local government gerrymandering. On 9 December 1968, O’Neill broadcast to the province, addressing the civil rights marchers in a bid to keep the violence from increasing. Shortly after, he fired William Craig and the immediate response was favourable, although this did not last. O’Neill finally decided to call a general election to ease dissatisfaction, which ultimately resulted in his resignation.

The End of Stormont and the imposition of direct rule in 1972 PDF

Dr Marc Mulholland, St Catherine’s College, Oxford

The 1970 Prevention of Incitement Act applied the English Race Relations Act (1965) to sectarian cases and the local government found itself generally emasculated and gerrymandering was forced out. Brian Faulkner, head of the Parliamentary Unionist Party, was responsible for the first inter-party meeting held at Stormont on 7 July 1971, with representative of the Ulster Unionists, Social Democratic and Labour Party, National Party and Northern Ireland Labour Party. All talk of political breakthrough came to an end on 12 July, and hostilities between the Army and IRA reached a breaking point. Bloody Sunday sparked rioting across nationalist Ulster and the national and international concern expressed over the violence brought a new urgency to British Government policy. At the end of March 1972, the Stormont Parliament was suspended.

Return to Archive

Other selected Northern Ireland resources

Gale is not responsible for external links.

BBC: “A State Apart”

Conflict Archive on the Internet

Troubled Images

© Bettmann/CORBIS 515931062; © Bettmann/CORBIS 514689376